This is a very easy question; it is very easy to answer, because this topic has been developed for a very long time and everyone is very interested in it. Moreover, I will say that this is the topic that led me to study the methodology of teaching foreign languages.

We have three sections.

Section 1. I will show you techniques that you can immediately apply in practice in your lesson.

Section 2. We will talk a little about the theoretical basis. I will tell you what to look at, what topics, and what materials to look for, so that you yourself can develop the skill of teaching children without explaining grammar.

Section 3. How we teach children a language without explaining grammar to them with the “Soroka” textbook.

Section 1

In this section, I show specific actions and comment on them. At the end, I will simply make a summary of the actions without commentary.

Examples are taken from the Akishina-Kagan book “Learning to Teach,” pages 133-136.

Step 1 extended — The teacher shows a picture and says: Девочка читает книгу.

It is better to listen with a picture, without a graphic version. That is, it is better to hear first than to read! Let me remind you that this is the very first introduction to this grammatical structure. The students are not familiar with it yet. Девочка читает книгу.

Step 2 extended — The students listen and repeat after the teacher: Девочка читает книгу.

As soon as we get acquainted with something for the first time, we immediately repeat it out loud. Once is enough for now.

Step 3 extended — The students remember what they have already studied before; they need it for support. So, they remember familiar models like:

Кто это? Это девочка. Что делает девочка? Девочка читает.

To help the students remember better, the teacher asks them questions.

To study this specific topic (which we are now illustrating), the students already need to know and use a certain number of transitive verbs; for example, писать, читать, знать, слушать and учить. They should know inanimate nouns and their gender forms. This is necessary for support when studying a new topic. I have written and spoken a lot about how to train the gender of nouns based on color, and I have a video about the Three Bogatyrs that I use as a teaching aid.

Step 4 extended — The teacher pronounces the word книгу, trying to emphasize the ending with her voice. The teacher’s task is to draw the students’ attention to the third element in the structure. What are the other two elements? Девочка and читает. The third element is a книгу.

Step 5 extended — The teacher pronounces structures of this type with the accusative case of the masculine gender: Она читает журнал. Он читает текст. Они смотрят телевизор.

Students listen and repeat after the teacher (you can use a picture). Let me remind you that the students are familiar with these verbs and already know how to conjugate them. The students are familiar with all the words (TV, etc.).

Here the teacher needs to remove the fear of the new form, which we have already become familiar with. Show that in the masculine gender everything is calm and nothing has changed. Well, let me remind you that by this time your students have already understood the difference in gender and know the gender endings.

Step 6 extended — The teacher needs to find out how the students understood the meaning of the third element. What words can they use? For example, you can make a joke: Ask, Это телевизор смотрит? The students answer: Нет! The teacher asks: Это текст читает? The students answer: Нет! You can take another phrase.

Step 7 extended — The teacher then gives examples with words of the neuter gender. He says: Она читает письмо. Он слушает радио. The students see that these are words of the neuter gender.

Step 8 extended — Finally, the feminine forms are given. The teacher says: Мы слушали музыку. Они читают газету. Оначитает книгу.

Step 9 extended — The students can derive the rule for forming the accusative case of the feminine gender themselves. If the students have difficulty, then you need to show them how the letter changes at the end (if this is a graphic version), or how the sound changes at the end (if they are learning by ear, without a graphic version). Here you can summarize the forms in a table. This is not necessary. You can also write down a sample phrase and translate it into your native language.

Step 10 extended — The next step is what question does the third member answer? Here, the students do not yet know the answer to this question. The teacher should show it to them. Ask a question and give an answer: Что она читает? Она читает книгу?

All the words are familiar to the students, and now the new form of the word book is familiar.

Step 11 extended — Students ask questions about the sentences they worked with today: Что они слушают? – Музыку. Что она читает? – Журнал. Что он пишет? – Письмо.

The primary consolidation of what has been learned occurs — its repeated use, preferably with the use of pictures.

Students ask questions. The teacher monitors the correctness of the phrases. Students’ mistakes, as a rule, appear due to inaccurate knowledge of the gender of nouns. I remind you that the gender of nouns can be studied based on color. I wrote and filmed a video about my Three Bogatyrs simulator. It was created specifically to train gender.

Step 12 extended — We have finished developing language competence and are starting to develop speech competence. Numerous questions are speech training.

First the teacher asks the students, then the students ask the teacher or each other these questions.

Я читают книгу, а вы?

Вы читали книгу или журнал?

Что вы читали?

Что вы слушали?

Что вы смотрели?

Step 13 extended — We continue to practice what we have learned in speech; you need to join the opinion.

Я читаю книгу. – Я тоже читаю книгу.

Step 14 extended — We practice speech. The task is to say the opposite.

Я читала книгу. – А я смотрела фильм.

Step 15 extended — We practice in speech. Situations. You are in a store and ask to show the things. Дайте, пожалуйста …

Step 16 extended — Students learn control of the use of the accusative case orally and in writing. Write down what you need to buy in the store, and then talk about it. Tell what you wrote, listened to and read this week. Tell the class about it. The teacher helps, of course.

Well, that’s it. I took this material from the book “Learning to Teach.”

Let’s draw conclusions.

1) Page 131 from the book “Learning to Teach”: Go from the meaning (sense) to the form. I don’t have a book means the absence of something.

2) Working on cases — pay attention to the verb control: look, watch, what? (a book, a film).

3) Teach students to ask questions for each case form: He looks at the teacher. Where is he looking? Who is he looking at?

It is useful to include repeated questions in the dialogues (“We didn’t hear”):

Он смотрит на преподавателя.

Куда он смотрит?

На кого он смотрит?

На преподавателя.

А! Он смотрит на преподавателя.

4) You need to work with the text, with the phrase, and not with a separate word or combination, and certainly not with the rules.

At the end of the first section, I will make a summary, as I promised: just techniques from the lesson without explanations.

1. The teacher shows a picture and says: Девочка читает книгу.

2. The students listen and repeat after the teacher: Девочка читает книгу.

3. The teacher asks questions: Кто это? Девочка. Что девочка делает? Девочка читает.

4. The teacher says the word книгу, trying to emphasize the ending with her voice.

5. The teacher says the following phrases: Он читает журнал Они смотрят телевизор. Они слушали текст. The students listen and repeat after the teacher. You can and should use a picture.

6. The teacher can joke: Это телевизор смотрит? Это книга читает? The students answer, нет!

7. Then the teacher says: Она читала письмо. Он слушает радио. The students listen and repeat, paying attention to the third word in the sentence.

8. The teacher says: Мы читали газету. Они слушали музыку. Ончитает книгу.

9. Students can derive the rules themselves. In the feminine gender, the form of the word changes. There was the letter A at the end, now it is the letter У. If students have difficulty, then you need to show them how the letter changes at the end (if this is a graphic version), or how the sound changes at the end (if they are learning by ear without a graphic version).

10. The teacher asks the students questions: Что девочка читает? (This was our very first sentence).

11. Students ask questions about the sentences they worked with today: Что они слушают? – Музыку. Что она читает? – Журнал. Что он пишет? – Письмо.

12. We practice in speech — numerous questions. First, the teacher asks them of the students, then the students ask these questions of the teacher or of each other.

Я читают книгу, а вы?

Вы читали книгу или журнал?

Что вы читали?

Что вы слушали?

Что вы смотрели?

13. We practice in speech — join in the opinion.

Я читаю книгу. – Я тоже читаю книгу.

14. Speech practice – say the opposite.

Я читала книгу. – А я смотрела фильм.

15. Speech practice – you are in a store, asking to show things. Дайте, пожалуйста …

16. Usage control: (a) Give me, please! (in a store); (b) answers to questions: What are you reading?

Section 2

The second section involves theoretical situations. I will tell you what to watch, what materials to look for to develop the skill of teaching children without explaining grammar.

In general, I am a boring person, I read a lot of books on the methods of teaching different languages in my time, and now I am broadcasting this. I am not developing anything new; I use what other methodologists have developed.

I have always (all my life in languages) been interested in this — how to teach in such a way that it would be possible to avoid studying grammar. This is how I came to the methods of teaching foreign languages, and then RFL (Russian as a Foreign Language).

Let’s see what they write in the book “Learning to Teach,” page 140. Deductive and inductive introduction of grammar:

1) Deductive — the teacher explains the rule and trains it with the audience. A classic example is the grammar-translation method.

2) Inductive — the students themselves “discover” the rule. This is exactly what we need. All teachers of the methodology note this. What children need is an inductive introduction of grammar.

There is another author from Russia, named Shchukin. He, like me, does not invent anything; he generalizes and tells you about it. In his book “Teaching Foreign Languages,” on page 178, Shchukin lists inductive methods of work.

All of these methods began to appear more than a hundred years ago; for example, the direct method. The developers were Berlitz and Pimsleur. Pimsleur is still working — they have an application for learning foreign languages. And so on.

But the fact is that no one uses these methods in their pure form anymore. Now eclecticism is used in full swing — when some elements (or several elements) are taken from each method and combined, creating new methods.

Section 3

(from my article on grammar)

Those who are familiar with my textbooks know that there are no grammar rules in them, and that all tables with endings are final. We finish studying the lexical and grammatical topic with them.

In the textbook “Soroka” we have many mini-dialogues. The students just needed to practice lexical and grammatical constructions in speech. What we read about in the book “Learning to Teach” are questions and answers.

“Soroka” is written for children. The main thing for me was not to scare the child with grammar. I also know that even if a child knows the rules, this does not mean that he can follow them. Therefore, I have a different approach — in “Soroka” we study the situation, and select words and grammar for the situation. For example, let’s take the topic “agreement of cardinal numbers with nouns.” This sounds scary even for an adult! If we take a small piece of this topic — two hours, three hours, four hours — then it becomes somehow more pleasant. We learned and practiced only four words: the numerals two, three and four, and the word hours. We learned and practiced their combinations. Let me remind you that in “Soroka” we study each form of a word as a separate word. We practiced the word combinations to remember them better. (“Soroka 1,” page 43)

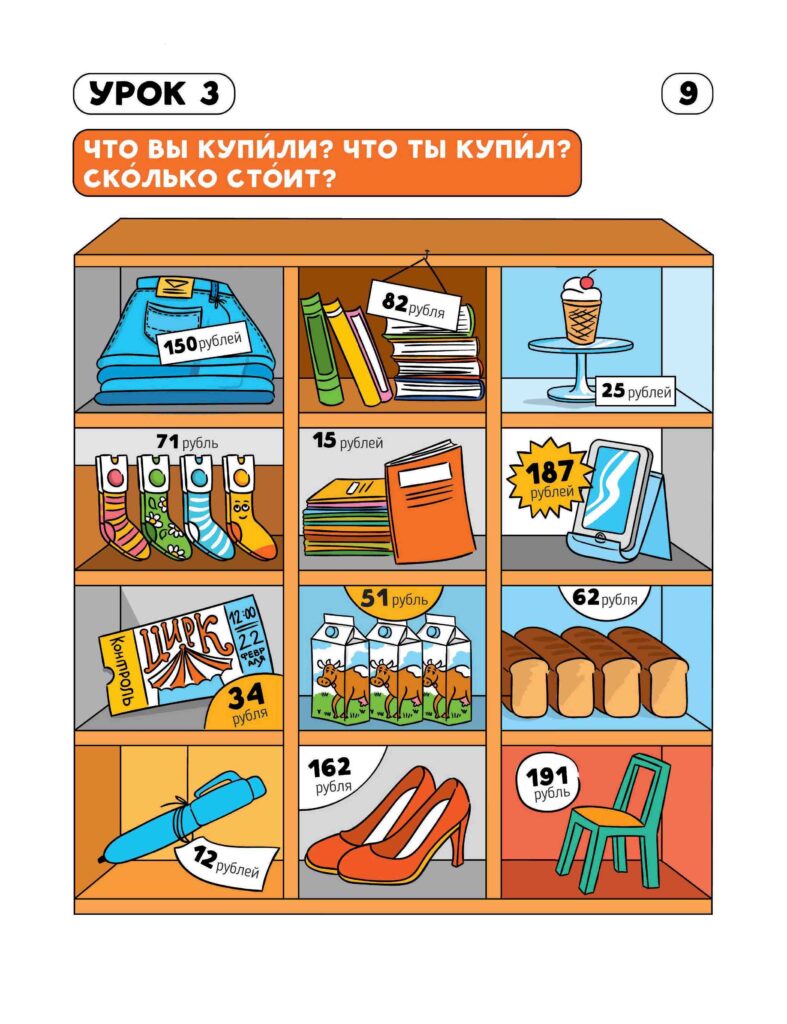

Then we continue with five hours, six hours, seven hours. We learned and practiced in “Soroka 1.” A little later, in “Soroka 3,” we go to the store and pay for our purchases. Our prices are 2 rubles, 5 rubles. Aha! We remember what we learned about hours and time, because there is the same rule there. (“Soroka 3” page 9)

(video about grammar)

(from my article about deriving rules)

I often suggest that my students derive rules themselves. I also write about this in the Teacher’s Book. Why do I do this? What does this give us in studying Russian as a foreign language with the “Soroka” textbook?

First, let’s look at the Teacher’s Book and see what we are talking about.

For example, Lesson 3, Session 2. I quote: The textbooks are open on page 11. The teacher reads the words out loud and asks the students how they can explain the difference in the word pairs идет/идут, спит/спят, сидит/сидят, etc. The student should say that when talking about one person, they use the words спит, сидит, читает, and when talking about several people, they use спят, сидят, читают.

Second example: Lesson 7, Session 1. Quote: After this, the teacher asks the students: “Maybe you’ve already guessed when to say зеленый, and when зеленая? The students give their own answers, making different guesses. If they find it difficult, then give a hint that they need to look at the last letters in the words.

For some teachers, this is very unusual. They are used to the teacher explaining the rule, and then the students practicing it. What happens when the teacher explains and the students “practice”? The students need to 1) remember the rule, 2) see the situation in which this rule is applied, and 3) apply this rule. In my opinion, this is very difficult. In my practice, most young students have rules in their heads in one place, and their implementation is in a completely different place. And it doesn’t matter whether they play chess, cross the road at a traffic light or learn Russian.

I suggest a different way. I suggest giving a situation and showing what exactly needs to be done in this situation. Secondly, I suggest observing the language, what is happening in it, and tracking patterns. What does this give us?

First, it develops observation and analytical skills. This is useful for developing the mind, and it helps in life.

Second, it is also useful because the student himself tries and is using his brain; it is active.

When you bring a rule on a silver platter, efforts are needed only to remember this rule and there is little motivation. This is passive perception.

If we derive the rule ourselves, then this is active perception; we remember it faster and for a long time. Because we have appropriated it, it is ours, we have put our energy into it and we have become co-creators.

Many will say that children do not know how to derive such rules; however, this is not true. Children’s word creation is precisely the result of observing language and deriving rules. Everyone has read Chukovsky’s “From Three to Five.” I have a video about deriving rules: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JcueiGVKcVo.

Children all over the world do this, not just Russian-speaking ones. They observe the language, draw conclusions and apply them. Most likely, children draw conclusions unconsciously. When you ask your students to draw rules, they will begin to do it consciously: that’s the only difference.

So, it is possible to teach without explaining grammar. Such methods have been developed for a long time, and they can and should be used in the classroom. This works for both children and adults. This is exactly how teaching is done in the “Soroka” textbook. All the best!