Over the past few years of teaching Russian as a foreign language, there was a breakthrough that impacted both approach to teaching Russian and attitude toward the language in general.

Could it be considered a revolution? You will know the answer later. Meanwhile, I suggest you take it slowly and remember what has happened in the teaching of Russian as a foreign language over the last six years.

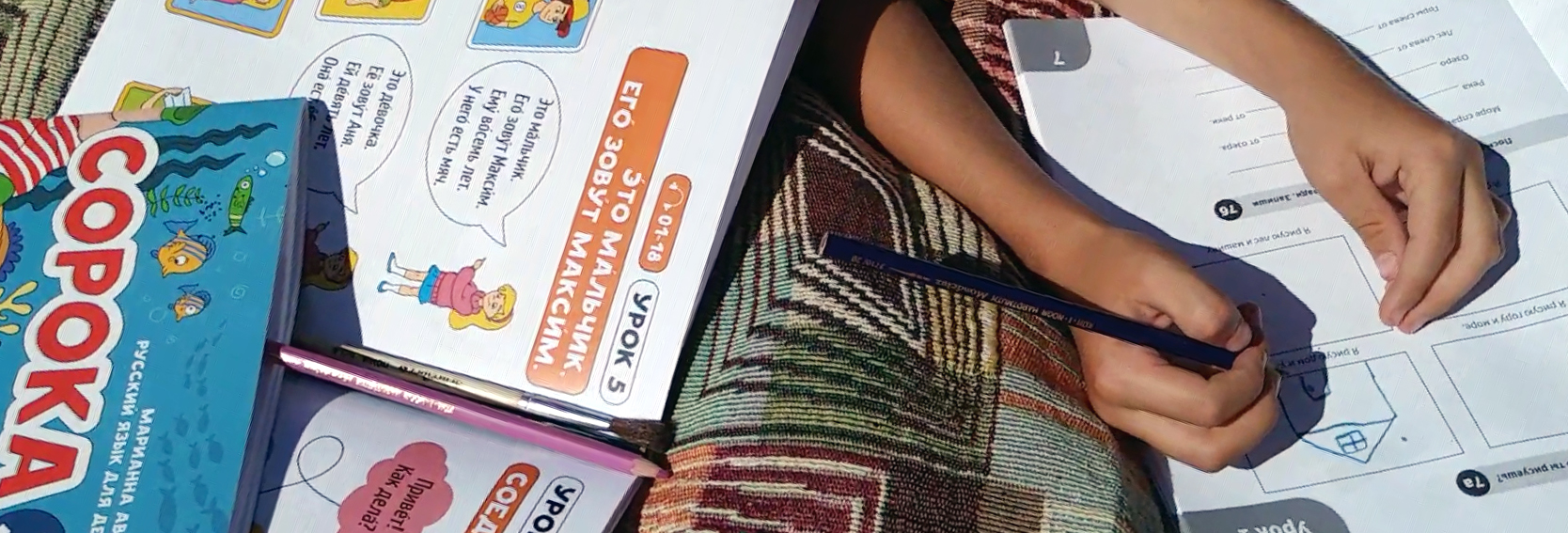

Why do I say over the last six years? That is how many years old my Soroka course turned in 2022. The first course appeared in February of 2016 and students are still loving it.

What has changed over the six years?

The attitude toward Russian language among native speakers changed.

Several years ago, my colleagues and old friends, particularly those who live in Russia, often asked me: “Do foreigners really learn Russian? Why do they do this?” Now the attitude toward Russian language between speakers has been changing. People don’t ask such a question as often. Russian people began to realize that foreigners learn Russian and their enthusiasm is steadily growing. They also started to realize how their native language is interesting and how rich its culture is. It is all worth learning. Soroka demonstrates that learning Russian can be as much fun as learning other modern and popular languages. It’s fascinating.

Educational books became closer to people.

Soroka was one of the first books where dialogue with the teacher appeared. You know that there are all kinds of teachers – mostly these are people who have any other profession and who don’t have teaching experience. That’s why when they conduct individual classes, they don’t know where to begin or how to arrange the lesson. Now such teachers have support. Initially the Teacher’s Book, with all of its detailed and methodical recommendations, was written for the Soroka course. Later on, a YouTube channel with instructional guidelines and additional videos for the course, as well as groups in social networks where teachers share their own recommendations and additional tools, appeared.

Modern pictures appeared in the books.

Kids of the 21st century need videos of the 21st century. In the Soroka course, we have only contemporary pictures. Kids look modern – without stockings and hats from the last century.

The approach to teaching changed.

As we conduct a lesson just one hour a week, we don’t have time for a linear approach, where one lesson follows another. We carry out lessons in the form of mini-cycles. The concept is that whether the student visited the previous lesson or not, he would gain a “drop” of knowledge. I often compare this approach to water. When drops of water accumulate, they create an ocean. We have the same thing with our lessons, but instead of an ocean we get the voluminous Russian language.

Lessons are conducted in the form of mini-dialogues.

The concept of mini-cycles has brought lessons in the form of mini-dialogues – students mainly learn words and phrases rather than rules. The Student’s Books turned into peculiar phrase-books.

To sum up: Over six years Russians realized that their language is valuable, that there are people in the world who are interested in it and who learn it. Illustrations and characters in the books became contemporary. The approach of mini-cycles appeared, which has brought lessons in the form of mini-dialogues. This approach has proven to be the most suitable for learning language one hour a week.

Some call it a revolution. From the perspective of transformations, I agree that the revolution occurred. But from the perspective of new teaching methods, there was no revolution; we assembled existing methods and adjusted them to our goals and tasks.