Games in lessons of Russian for children and adults — what are they for, what is their advantage, when and how to play? The topic about games is a difficult one. Later I’ll tell you why.

Let’s start with how to play

In the Teacher’s Book for Soroka 1, there are games for studying numerals in Russian.

Game 1. Drumroll

The teacher taps a pencil on the table or claps his hands, the students listen carefully to how many times the teacher knocks, and they call out the number in Russian. For example: the teacher claps five times, and the students respond with “Five!” We achieve spontaneity of speech; this is our goal in this case.

Game 2. How many? Сколько?

The teacher clutches several small objects in his fist. For example: matches. He asks the students, “Сколько?” (“How many?”) Students call out the quantity in Russian. (This is important!) They are trying to guess. When everyone has spoken, the teacher opens his fist, shows the number of matches, and everyone counts together. The one who names the correct number wins.

Game 3. “Hide and seek in the castle. Tourists and the ghost.”

This is a game from Soroka 2, page 20. Usually, we don’t allow yelling in class — but here, please yell. From a methodological point of view, in this game the participants must hear (!) the difference between different cases: в подвал — в подвале; на крышу — на крыше; в гостиную — в гостиной. One player is a ghost, and the rest are tourists visiting the castle. The ghost makes a wish for the room in which it is hiding, and writes it on a card. Tourists walk around the castle (you can move the chips) and say, “I’m in the kitchen,” or “I’m going to the basement.” There’s a ghost in our basement. When a tourist says, “I’m in the basement,” this is the time for the ghost to “scare” the tourist by shouting, “Ah!” At this point the game starts over, but another student becomes the ghost.

Let me remind you that this is a game from Soroka 2. We play it when we have gone through the names of the rooms in the house, the prepositional and accusative cases, and can distinguish я иду в комнату — я в комнате. You don’t have to take the playing field from Soroka; you can draw a plan of a house or apartment yourself, or download it online.

Game 4. This is a game of repeated repetition.

So, how do we play? The student makes a guess about what he eats or drinks, writes it on a card, and gives it to the teacher. You understand why he should do this, right? Did you guess it? Write to me in the comments.

I note that this is an ideal way to say all the words and phrases many times. People usually don’t like to repeat themselves many, many times, but we need this to practice. So, we practice it in games. For example, the words “я ем,” “ты ешь,” “я пью” and “ты пьешь.” I call it drilling, and I have a video about drilling. We need this kind of training to translate it into speech. When you’ve said it a million times, it will pop up in conversation. You’ll see.

So, let’s start the game. The group members begin to ask “ты ешь хлеб?” “ты пьешь кофе,” the student answers. The game is over when the group guesses what the student is up to.

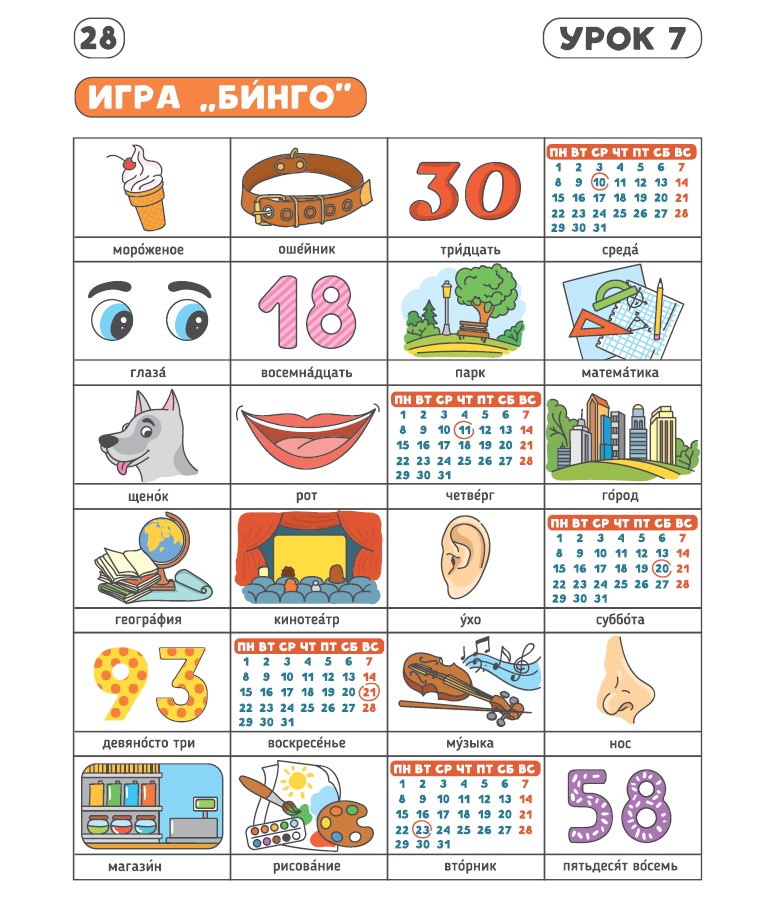

Game 5. My students’ favorite game is bingo.

This game includes both listening and speaking. With this game it is very good to repeat learned words.

For those who haven’t played, I’ll explain what to do. Here is a large field to play.

Each student receives a small piece of this field. The presenter has a stack of cards. The presenter pulls out one card at a time and says out loud what is drawn on the card. The student looks at his piece of the field. If he has this word, then he places a chip on it (maybe a button or even a bean). When all of the fields on the card are covered, the student shouts “Bingo!” He won. As I already said, this is a listening game and with this game it is very good to repeat learned words.

Did you like this game? Write in the comments.

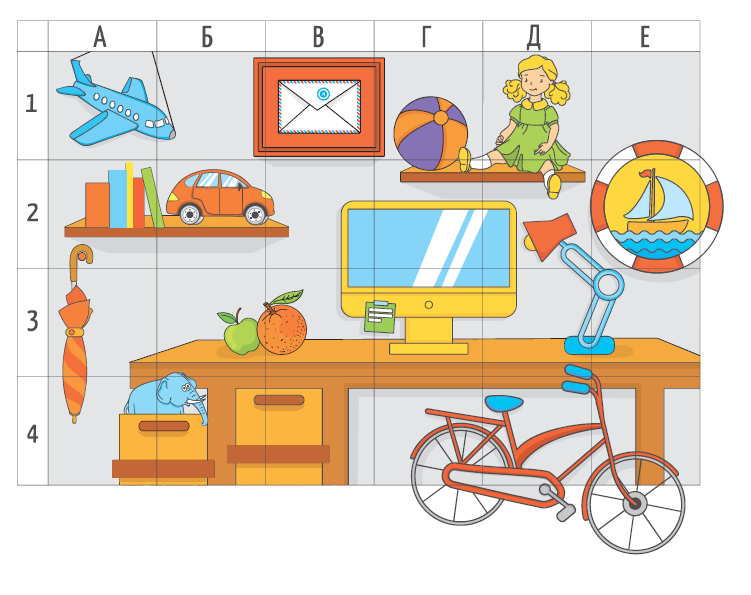

Game 6. Coordinate grid.

There is a picture in the textbook, but you can organize a similar playing field from anything and lay out both pictures and real objects.

Here we have communication, and a completely meaningful conversation, and the consolidation of new words, and the repetition of old ones learned a long time ago. Do you like it?

Game 7

Another game that I really like, and which helps in learning gender and number agreement. This game is also from the Teacher’s Book for Soroka 1.

There are pencils of different colors on the table. Students name red pencil, жёлтый карандаш, зелёный карандаш, красный карандаш, etc. The teacher covers the pencils with a sheet of paper, removes one pencil so that the students do not see it, and opens the pencils. The students’ task is to say what is missing.

It turns out that a complex grammar topic like agreement in gender and number, and such an interesting solution is a game. The students are playing, with no idea that this is an exercise. And that’s exactly what we wanted. Our task is indirect goal setting. Students think that they are doing one thing, but in fact they are doing something completely different — which we need for learning, and which is correct from a methodological point of view.

The second part is When we play games in the Russian language lessons.

This is the simplest answer.

First. We play during warm-up. Students (both adults and children) need to tune in to the lesson, move from one reality to another, switch from one language to Russian. Games will be our bridge. It’s easy and simple. It’s like in the movies. In cinema, we need to get to know the hero, find out who he is and what he does. The opera has an overture. We also enter the lesson.

Second. We also play during the end of the lesson. Everyone is already a little tired (and the teacher, too). We need to relieve tension and play so that everyone leaves in a good mood. For motivation, it is very important that students leave the lesson in a good mood.

Third. We play when we need to bring some skill to automaticity. Students do not like to repeat the same thing over and over again. To make repetition interesting and not just boring, we include games.

The fourth and last time, we play — when students are tired and need to change the type of activity. We teachers also get tired, but we have a lesson, we need to teach, we can’t just refer to fatigue and say, “I am sick and tired of you all.” We need to keep working, so we play.

All of the games described (and many others) are in all of Soroka’s textbooks: Soroka 1, Soroka 2, Soroka 3. The games are described not only in textbooks: Many of them are in Teacher’s Books. Watch, play.

Well, now I’ll tell you why I think this is a difficult topic. Because the topic is hackneyed. Everybody and his brother wrote about gamification. But this is normal; since they write it, it means that teachers need it. I regret that now everything is called a game, even something that is not a game at all. Some teachers even think that tests are work games. I saw how children sadly dropped their shoulders when they heard, “And now the game.” That’s why it was unpleasant for me to talk about this topic.

Fortunately, now everyone is passionate about artificial intelligence. This is a new toy, but I don’t know for how long. Also fortunately, the games have been left alone, and you can play normally in class. Now you know my opinion; I’m interested in hearing yours. Write in the comments what you think.

Best wishes!

Очень полезные игры. Методически правильно. Спасибо.

Спасибо за ваш комментарий!