Today we will talk about:

- age and how it affects teaching Russian as a foreign language to children

- what modern children want from lessons

- who we are working with — children or parents

- two books and why I recommend them

- what to do with grammar

- age and how it affects teaching Russian as a foreign language to children

The age of the student affects not only the teaching of Russian as a foreign language; age affects teaching in general. People are different at 3 years old than they are at 60 years old. I also had an article about how to teach Russian as a foreign language to people over 50.

Children are very different at different ages. Tactility is essential for children up to about 7 years old — they need to touch, move, and break everything. This is normal. This is what you need to base your teaching on.

Therefore, it is inadvisable to teach online because there is nothing to touch. Still, there are teachers who teach online.

There is a lot of literature that describes in detail the stages of speech development in children, what happens at what time. A little later, I will show you two books that I recommend.

What do modern children want from RFL lessons?

- to influence their learning

- entertainment, ease

- quick results

According to Russian linguist Alla Akishina, a child learns language by listening and communicating, not by analyzing.

Much is being written about learning through games. Games are important and necessary, and you can really teach a lot by using them. You need to know why you use these games and how best to use them — playing with purpose. By the way, my video about games in RFL lessons already has 19,000 views; here is the link. People are interested in this topic. In my video, I just list the games without classification. In my blog, I have an article about games in RFL lessons; here is the link. There is a classification of games: memory games (lotto and bingo for me) and guessing games. This classification can be found in the book “Learning to Teach” by Alla Akishina, p. 223.

Children and adults like to play in class. Teenagers — not so much.

Treat games as exercises, but do not call exercises games.

Working with parents is even more important than working with children. For one thing, parents pay you for your work, so it is important to establish contact with them and maintain good relations.

It is important to explain to parents what is happening in class and why we do this or that exercise. This is maintaining feedback on the one hand, because parents are interested in knowing what is happening in class. When parents understand what is happening, they can support their child in the activity; for example, do not let him quit.

How can you explain to parents what is happening in class? The necessary words can be taken from literature. A smart author explained it to you; you explain it to your parents. All knowledge is always transferred this way — from person to person; no other way has been invented yet. A teacher simply must know what is written for parents. First, you are a beginner teacher; you will not understand literature on psychology overnight. Thus, start with something easier at the initial level. Books for parents are just entry-level pedagogy. Then you will move on to more professional reading. This is the first thing. Second, reading such literature gives you the language, the words, for communicating with parents. You have read a book for parents, and you have understood how and what to say in order to convey your thoughts to them. I often hear this from my blog readers and YouTube viewers: “You gave me the words to talk to the parents of my students, to explain to them what and how we do in class.”

Two books

I always recommend books by Alla Akishina. And this time I have two such recommendations. One is “Learning to Teach,” and the other is “Learning to Teach Children the Russian Language: 111 Answers to Parents’ Questions.”

The second book is written for parents, but it will also be very useful for beginning teachers to study, especially the detailed description of the stages of speech development in children and how to work with them at each stage. Read, learn.

What about grammar? The teacher needs to know the grammar of RFL; the student does not need to. I have a video on how to teach RFL without grammar.

Akishina and Kagan write about this:

- Go from meaning (sense) to form. “I don’t have a book” means the absence of something.

- When working on cases, pay attention to verb control: look — watch — what? (a book, a film).

- Teach students to ask questions for each case form: He looks at the teacher. Where is he looking? Who is he looking at?

It is useful to include repeated questions in the dialogues (“We didn’t hear”):

- He is looking at the teacher.

- Where is he looking?

Who is he looking at?

- At the teacher.

- Ah! He is looking at the teacher.

- You need to work with the text, with the phrase, and not with a separate word or combination, and certainly not with the rules.

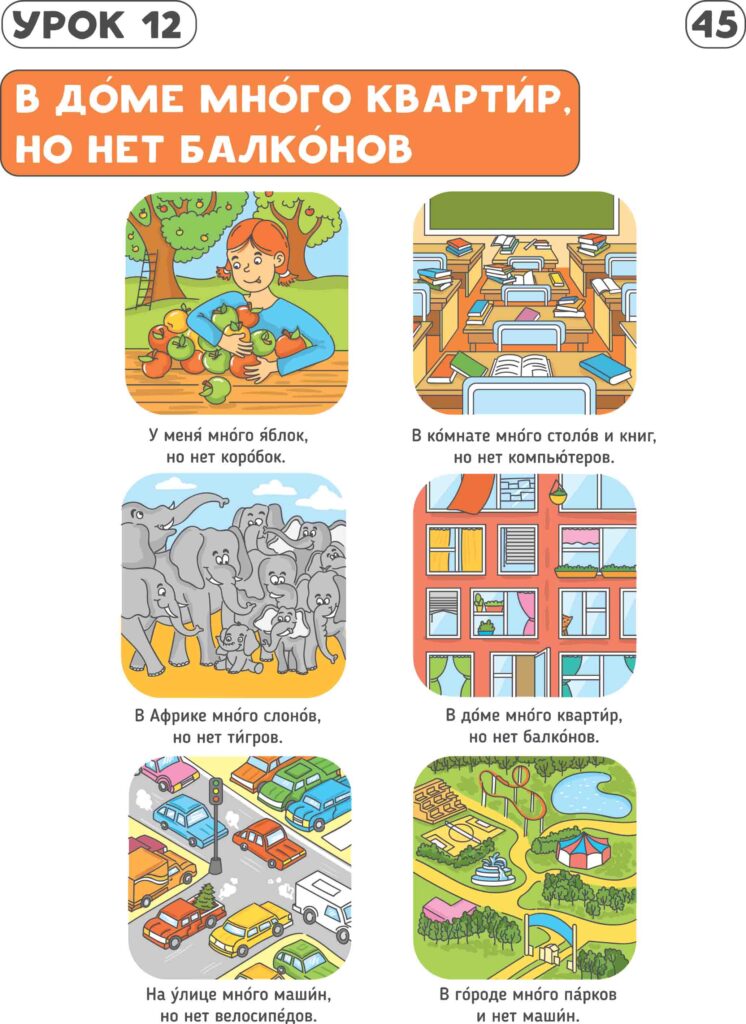

This is exactly how my Soroka textbooks are structured. For example, the genitive case. We simply count objects: one — many.

(This is page 41 from the Soroka 2 textbook.)

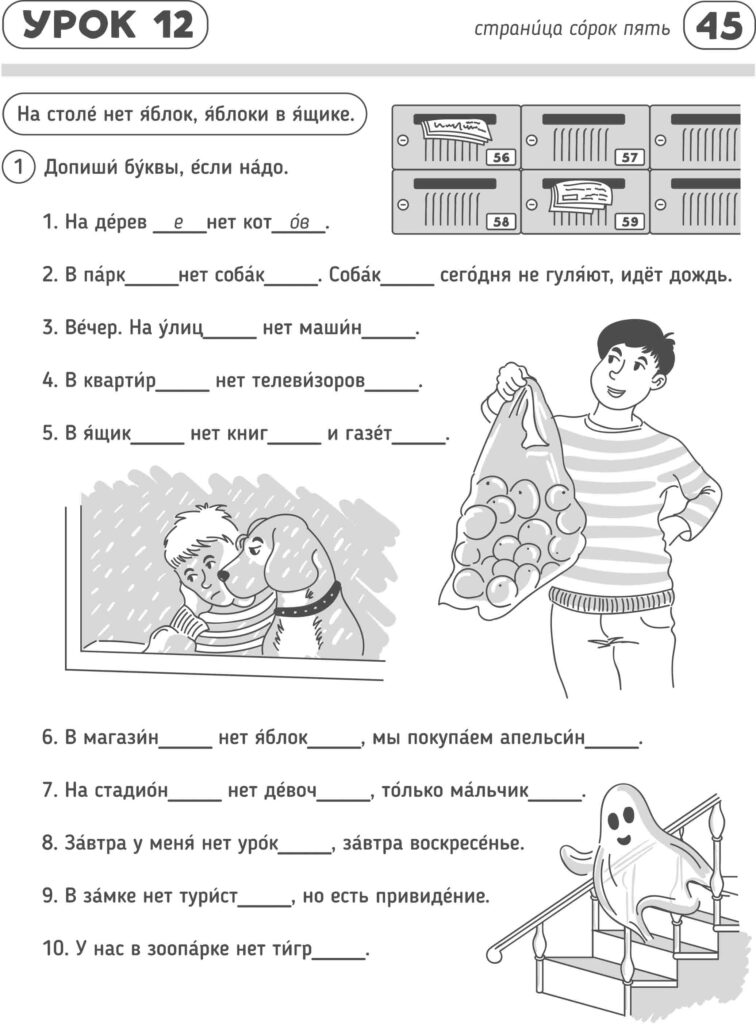

Then we say what we have and what we don’t. We constantly ask questions and give answers to them. Look at the pages from the Soroka 2 textbook. Throughout the lesson we look at pictures, count objects, and talk about them.

(Soroka 2 textbook, page 45)

At the end of Soroka 2, we have a comic strip that contains everything we know about the genitive and prepositional cases. Children see the situation. You have learned that in “many cars” and “no cars,” the word “car” changes in the same way.

Well, that’s it. To sum up. Teaching RFL to children differs from teaching it to adults. Children are also not homogeneous; there is a very strong difference in age. When you work with children, you also work with parents at the same time. Yes, we do not teach grammar to children. Write questions in the comments.